| party | fault | Damages | Reallocation | Adj Damages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 40% | $16,000 | $4,000 | $20,000 |

| B | 30% | $12,000 | $3,000 | $15,000 |

| C | 10% | $4,000 | $1,000 | $5,000 |

| D | 20% | $8,000 | $0 | $0 |

Comparative Negligence and High/Low Agreements

Introduction

In this handout, we’ll discuss the comparative negligence defense as well as high/low agreements.

Imagine a negligence claim brought by a plaintiff against one or more defendants in which all the parties are partly at fault for the plaintiff’s injury, i.e., each party breached the standard of care in way that caused or contributed to the injury; and each party is held responsible for the injury as a result.

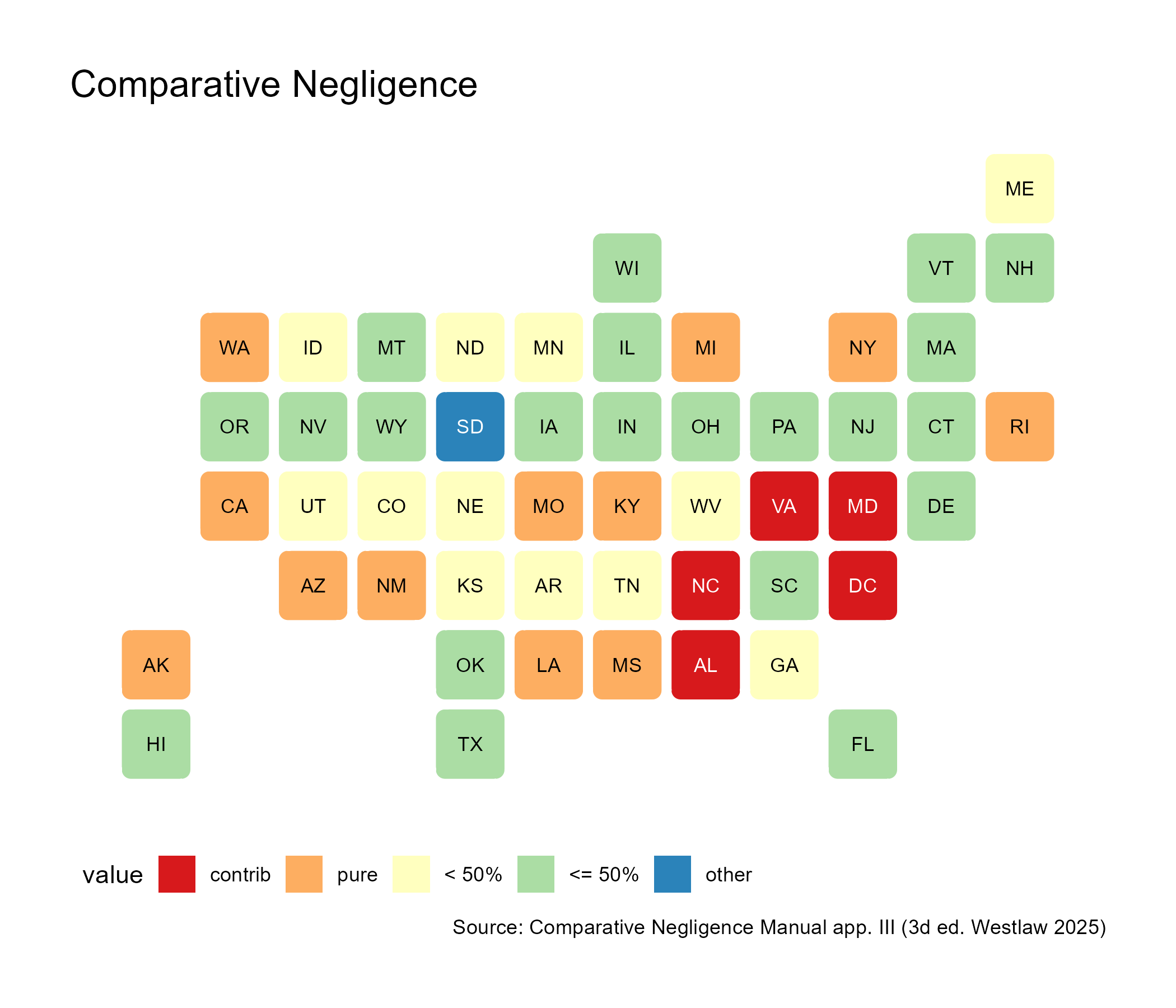

Under the contributory negligence defense, since the plaintiff was partly at fault, that plaintiff would have recovered nothing. As Figure 1 depicts, in the 1970s and 1980s, many States moved to replace contributory negligence with a comparative negligence defense, mostly by legislative action (Comparative Negligence Manual 2025, app. III).

Today, most States generally follow a comparative negligence approach for common-law negligence claims.

Under comparative negligence, the plaintiff’s recovery depends on how much fault a jury assigns to the parties. Typically, a court instructs the jury to assign percentages of fault to each liable party so that those percentages add up to 100.

For example, consider this model jury instruction from the Pattern Jury Instructions Committee of the Association of Justices of the Supreme Court of the State of New York:

If, however, you find that the plaintiff (decedent) was negligent and that (his, her) negligence contributed to causing (the accident, injury, [or other appropriate characterization of the event]), you must then apportion the fault between the plaintiff (decedent) and the defendant [and, where appropriate, AB, a third person].

Weighing all the facts and circumstances, you must consider the total fault, that is, the fault of both the plaintiff (decedent) and the defendant [and where appropriate, AB] and determine what percentage of fault is chargeable to each. In your verdict, you will state the percentages you find. The total of those percentages must equal one hundred percent.

N.Y. Pattern Jury Instr. - Civil 2:36 (2020).

Then, each party is responsible for an amount of money that equals total damages multiplied by that party’s assigned percentage of fault. For example, in a lawsuit with one plaintiff and one defendant, if damages totaled $100, and the jury found the plaintiff and defendant 20% and 80% at fault respectively, the plaintiff’s recovery is $80. Under contributory negligence, plaintiff’s recovery would have been $0.

Multiple Defendants

Applying comparative negligence gets a bit more complicated if there is more than one defendant assigned a share of fault.

Suppose a lawsuit with three liable defendants (D1, D2, D3) and a plaintiff (P). Before comparative negligence, States would have assigned each liable defendant a pro rata share of damages. So, if total damages were $100, each of those three defendants would have paid \(\frac{\$100}{3}\) = $33.

Under comparative negligence, the jury assigns percentages of fault (\(s\)), such that \(y_{i} = A \times s_{i}\), where y = the required payment for each party i (each defendant and plaintiff) and A = total damages awarded.

For example, if A = $100 and \(s_{D1} = 51, s_{D2} = 34; s_{D3} = 15; s_{P} = 0\), then defendants 1, 2, and 3 each owe $51, $34, and $15, respectively.

If A = $250 and \(s_{D1} = 51, s_{D2} = 34, s_{D3} = 15, s_{P} = 0\), then defendants 1, 2, and 3 each owe $127.50, $85, and $37.50, respectively.

If A = $100 and \(s_{D1} = 51, s_{D2} = 24; s_{D3} = 15; s_{P} = 10\), then defendants 1, 2, and 3 each owe $51, $24, and $15, respectively, for a total of $90 for the plaintiff to recover.

Pure vs. Modified

Most States with comparative negligence typically have either the pure version or a modified version (Figure 2).

Under pure comparative negligence, the percentage of fault assigned to the plaintiff does not affect recovery. For example, if plaintiff is 90% at fault, that plaintiff can still recover 10% of damages from the defendant.

Under modified comparative negligence, if the jury assigns some non-zero percentage of fault to the plaintiff, that percentage may affect whether the plaintiff can recover anything at all. In some States with modified comparative negligence, plaintiff recovers $0 unless plaintiff’s fault is less than 50%. In other “modified” States, plaintiff recovers $0 unless plaintiff’s fault is less than or equal to 50%. E.g., Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S\) 52-572h(b); Fla. Stat. \(\S\) 768.81(6).

To illustrate how modified comparative negligence works, consider this problem:

There has been an accident in which A has suffered damages of $40,000 and has sued B, C, and D. Trial has established that the relative shares of fault are A-51%; B-29%; C-15%; and D-5%. Under Iowa law, what may A recover from B and C?

Answer: A recovers nothing, because Iowa has modified comparative negligence:

Contributory fault shall not bar recovery in an action by a claimant to recover damages for fault resulting in death or in injury to person or property unless the claimant bears a greater percentage of fault than the combined percentage of fault attributed to the defendants, third-party defendants and persons who have been released pursuant to section 668.7, but any damages allowed shall be diminished in proportion to the amount of fault attributable to the claimant.

Iowa Code \(\S\) 668.3(1)(a). Here, A bears “a greater percentage of fault than the combined percentage of fault attributed to” B, C, and D (51% > 49%). Accordingly, A recovers zero.

Reallocation Among Parties

What happens if one of many defendants found at fault cannot pay what it owes in damages because of insolvency?

Well, some States allow for proportional reallocation of an insolvent defendant’s share among the remaining parties. This matters most in States where the plaintiff cannot avail itself of joint and several liability. Even if they can, reallocation can affect how much a defendant can recover from another defendant in a contribution action.

To illustrate, consider the following problem:

There has been an accident in which A has suffered damages of $40,000 and has sued B, C, and D. Trial has established that the relative shares of fault are A-40%; B-30%; C-10%; and D-20%. At trial, it now appears that D is insolvent. Under the Uniform Comparative Fault Act (1977) (“UCFA”), what may A recover from B and C?

Under section 2(d) of the UCFA, D’s “uncollectable” share may be reallocated “among the other parties, including a claimant at fault, according to their respective percentages of fault.”

Here, the remaining parties are A, B, and C, and they together comprise 80% of the remaining fault. Accordingly, of the amount to be reallocated ($8,000), each remaining party bears its initial share of fault divided by 80%. For example, after reallocation, B owes $15,000 to A, that is, $12,000 plus \(\frac{30\%}{80\%}\) of D’s share ($3,000 = \(\frac{30\%}{80\%} \times \$8000\)). A’s total recovery is $20,000.

In contrast, some States reallocate only based on the remaining defendants’ shares of fault. E.g., Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S\) 52-572h(g). Here, if we had reallocated only among the remaining defendants, we’d exclude D (the insolvent defendant) and A (the plaintiff), leaving B and C, who are together are only 40% at fault.

| party | fault | Damages | Reallocation | Adj Damages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 40% | $16,000 | $0 | $16,000 |

| B | 30% | $12,000 | $6,000 | $18,000 |

| C | 10% | $4,000 | $2,000 | $6,000 |

| D | 20% | $8,000 | $0 | $0 |

Here, B would have owed $18,000 to A, that is, $12,000 plus \(\frac{30\%}{40\%}\) of D’s share (= $6,000)). And B would have owed $6,000 to A, that is, $4,000 plus \(\frac{10\%}{40\%}\) of D’s share (= $2,000)). A’s total recovery would have been $24,000.

Regardless of whether reallocation occurs among the remaining parties or the remaining defendants, any defendant now have a reason to pull into the lawsuit people or organizations who are not (yet) defendants, hoping that, as a result, their own share of fault (if any, allocated or reallocated) will decrease. E.g., Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S\) 52-102b (providing the only procedure by which a defendant may add a person who is or may be liable pursuant to section 52-572h for a proportionate share of the plaintiff’s damages as a party to the action).

High-Low Agreements

In a high-low agreement, a defendant agrees to pay plaintiff a minimum recovery in return for plaintiff’s agreement to accept a maximum amount regardless of the outcome of the trial. If the jury award falls between the minimum and maximum, the parties agree to accept that outcome. In this way, the parties can manage the liability risk associated with a trial.

Example 1 : During the trial, P and D enter into a high-low agreement ($100,000-high, $40,000-low). After trial, the jury returns a verdict in which it finds D to be 97% at fault and P to be 3% at fault, and awards $500,000. Because of the high-low agreement, D must pay $100,000 to P, not $485,000.

Example 2 : During the trial, P and D enter into a high-low agreement ($100,000-high, $40,000-low). After trial, the jury returns a verdict in which it finds D to be 97% at fault and P to be 3% at fault, and awards $20,000. Because of the high-low agreement, D must pay $40,000 to P, not $19,400.

Some States require such agreements to be disclosed to the court and the parties in cases with multiple defendants. E.g., In re Eighth Judicial Dist. Asbestos Litigation, 8 N.Y.3d 717, 722-23 (2007). No State, however, expressly requires disclosing high/low agreements to the jury. In contrast, California, for example, provides: “Neither the existence of, nor the amounts contained in, any high/low agreements may be disclosed to the jury.” Cal. Code Civ. Proc. \(\S\) 630.01(b) Why do you suppose that is?

A Mary Carter agreement is a particular kind of high/low agreement between plaintiff and defendant. “Mary Carter” comes from Booth v. Mary Carter Paint Co., 202 So. 2d 8 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2d Dist. 1967). (Such agreements are now void in Florida. Dosdourian v. Carsten, 624 So. 2d 241 (Fla. 1993).) A Mary Carter agreement typically has the following features:

- the agreement is secret;

- the settling defendant remains in the lawsuit, but its total liability is limited by the agreement;

- the settling defendant guarantees the plaintiff a fixed monetary recovery, regardless of the outcome of the litigation; and

- the settling defendant’s liability (what it owes the plaintiff) decreases in proportion to the increase in the non-settling defendant’s liability.

To illustrate, suppose P sues D1 and D2 in tort for $100. P and D1 secretly agree that D will pay P at a maximum of $50, regardless of the outcome, and pay $1 less for every dollar above $60 that D2 pays as part of final judgment.

Some States ban Mary Carter agreements (e.g., TX, FL, NV, WI), but some permit them under certain conditions (Vaeth 2025).

Conclusion

In this handout, we discussed the comparative negligence defense as well as high/low agreements. Where the lawsuit involves one plaintiff and one defendant, comparative negligence (pure and modified) are relatively easy to apply. Things get just a bit complicated with multiple defendants. Finally, high/low agreements are one way that parties can manage their uncertainty about the jury’s allocation of percentages of fault.

Colophon

All figures were produced with R version 4.5.2 (2025-10-31 ucrt) and various packages, including ggplot 4.0.0 and statebins 1.4.0 (Wickham 2016; Rudis 2020).