Punitive Damages in Connecticut

Background

Courts have adopted different ways of deciding whether a punitive damages award in a particular case is excessive as a matter of law. Most courts apply a “shocks the conscience” standard on a case-by-case basis in deciding whether punitive damages are excessive as a matter of law.

Legislatures often set a maximum (cap) award for punitive damages in a particular case. Thus, for any punitive damages award \(x\), what the plaintiff actually recovers is some function of that award and a threshold \(\tau\) set by statute.

In the simplest approach, the legislature sets the cap by specifying a nominal monetary amount for any one case. So, if the statuory damages cap is $200,000, then

\[ \tau = 200,000\] \[f(x,\tau) = \begin{cases} \tau, & \text{if } x > \tau \\ x, & \text{if } x \leq \tau \end{cases}\]

Some legislatures take the portion of a punitive damages award over a certain amount and splits it between the plaintiff and the government.

To illustrate, consider Utah. There, for any punitive damages awarded, for the “first $50,000, judgment shall be in favor of the injured party” and then “any amount in excess of $50,000 shall be divided equally between the state and the injured party.” Utah Code § 78B-8-201(3)(a). Put another way,

\[\tau = 50,000\]

\[f(x, \tau) = \begin{cases} 0.5(x - \tau) + \tau, & \text{if } x > \tau \\ x, & \text{if } x \leq \tau \end{cases}\]

So, suppose you are the plaintiff’s lawyer in a tort lawsuit in Utah where the jury has awarded $200,000 in compensatory damages and $575,000 in punitive damages. Under Utah Code § 78B-8-201, what is the most in punitive damages your client can receive? Answer: $312,500.00.

Some Legislatures may make the punitive damages cap depend on the amount awarded in the case for compensatory damages (\(z\)). For example, if any punitive damages award cannot exceed three times what was awarded for compensatory damages \(z\), then

\[\tau = 3z\] \[f(x, \tau) = \begin{cases} \tau, & \text{if } x > \tau \\ x, & \text{if } x \leq \tau \end{cases}\]

So, suppose you are the plaintiff’s lawyer in a tort lawsuit in this jurisdiction. The jury has awarded $200,000 in compensatory damages and $575,000 in punitive damages. Under this law, what is the most in punitive damages your client can receive? Answer: $575,000.00.

With these approaches, calculating the cap is easy so long as we already know the inputs (e.g. the compensatory damages award) and on what the legislature wants the cap to depend.

Connecticut

In other States, what the plaintiff can recover in punitive damages depends on something that no one has yet found, and so further litigation occurs over that issue. That’s what happens in Connecticut. There, the common law rule is that punitive damages is limited to plaintiff’s litigation expenses (including reasonable attorney fees) minus taxable costs – the subset of litigation-related costs or fees specified by statute that a prevailing party in a lawsuit can sometimes make the losing side pay, see Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S \S\) 52-243, 52-257. Plaintiffs seeking common-law punitive damages in Connecticut must present evidence in support at the same time they try to prove liability in the underlying tort claim. Berry v. Loiseau, 223 Conn. 786, 831 (1992). Evidence of the plaintiff’s litigation expenses can include, for example, the plaintiff’s contingency-fee agreement with their attorney.

Under this approach, the jury only decides whether the plaintiff has shown the prerequisites for eligibility for punitive damages. If so, then the trial judge decides how much counts as, for example, “reasonable attorney fees” in the particular case. While this does set the maximum award, it is not a cap on the trial judge’s discretion, because the trial judge must decide what counts as “reasonable attorneys fees” and other litigation costs in the first place and cannot award more or less than amount.

How did Connecticut adopt its unusual common-law rule for punitive damages? It appears to have existed in Connecticut for over a century. It arose in two steps: (1) the Court considered the availability of punitive damages as a reason to allow plaintiffs to have damages awards cover litigation expenses; and (2) punitive damages then became limited to an amount that would cover litigation expenses.

First, in Linsley v. Bushnell, 15 Conn. 225 (1842), Connecticut’s Supreme Court of Errors (the predecessor to the Connecticut Supreme Court), held that a trial judge had not erred by instructing a jury that, in estimating damages, it could consider “the necessary trouble and expenses of the plaintiff” in bringing his lawsuit.

The Court first observed the juries could and had awarded “vindictive damages, or smart money . . . in cases of wanton or malicious injuries.” The Court then reasoned that, in cases of wanton or malicious injuries, it made little sense to permit vindictive damages, which by definition go beyond the amount of actually suffered, yet deny the plaintiff “a right to recover an actual indemnity for the expense to which the defendant’s misconduct has subjected him.” Although some might presume that awards of taxable costs could in theory fully cover litigation expenses, “every client knows, as a matter of fact, they are not. And legal fictions should never be permitted to work injustice.”

Dissenting on this point, Justice Waite complained about asymmetry: Why should the plaintiff be allowed to recover expenses, if he prevailed, but a defendant could at best recover no more than taxable costs for its expenses for defending a lawsuit? Besides, he added: If taxable costs were in fact “inadequate, the remedy is with the legislature.”

Second, the Court later declared without much explanation that litigation expenses were the only basis for a punitive damages award at common-law. In Burr v. Town of Plymouth, 48 Conn. 460 (1881), the Court observed that there should be “some limit” to punitive damages; that “no case in our courts has gone further than allowing the plaintiff, in addition to compensation for his personal injury and suffering or loss of property, the expenses of his suit, not including the taxable costs”; and that neither “principle” nor “any decision in this state” justified letting juries go beyond actual damages suffered and award punitive damages at their discretion. This Court simply didn’t refer to the idea that punitive damages should be proportional to the degree of moral blameworthiness of the defendant’s conduct, let alone why litigation expenses might poor predict a proportional punitive-damages award.

Some years later, the Court simply stated: “[Litigation] expenses in excess of taxable costs . . . limit the amount of punitive damages which can be awarded.” Maisenbacker v. Society Concordia, 71 Conn. 369 (1899) (citations omitted). Then, a few years later, the Court declared: “In this state the common-law doctrine of punitive damages, . . . if it ever did prevail, prevails no longer. In certain actions of tort the jury here may award what are called punitive damages, because nominally not compensatory; but in fact and effect they are compensatory, and their amount cannot exceed the amount of the plaintiff’s expenses of litigation in the suit, less his taxable costs.” Hanna v. Sweeney, 78 Conn. 492, 492 (1906)(citing Maisenbacker).

In 1984, the Connecticut Supreme Court reaffirmed the rule limiting common-law punitive damages to the expense of litigation less taxable costs. It justified that rule as striking

a balance-it provides for the payment of a victim’s costs of litigation, which would be otherwise unavailable to him, while establishing a clear reference to guide the jury fairly in arriving at the amount of the award. Further, although our rule is a limited one, when viewed in light of the ever rising costs of litigation, our rule does in effect provide for some element of punishment and deterrence in addition to the compensation of the victim.

Waterbury Petroleum Products, Inc. v. Canaan Oil and Fuel Co., 193 Conn. 208, 237-38 (1984) (footnote omitted). The Court added that the rule avoids “the potential for injustice which may result from the exercise of unfettered discretion by a jury.” Id.

This reasoning relies on three premises:

- A plaintiff’s litigation costs typically differ from what would have been a proportionate punitive damages award;

- That difference is worth avoiding the risk of juries issuing disproportionate punitive damage awards; and

- Despite this difference, a plaintiff is still better off as compared to a rule that bans common-law punitive damages completely.

What would it take to show these premises to be sound or unsound?

Other States

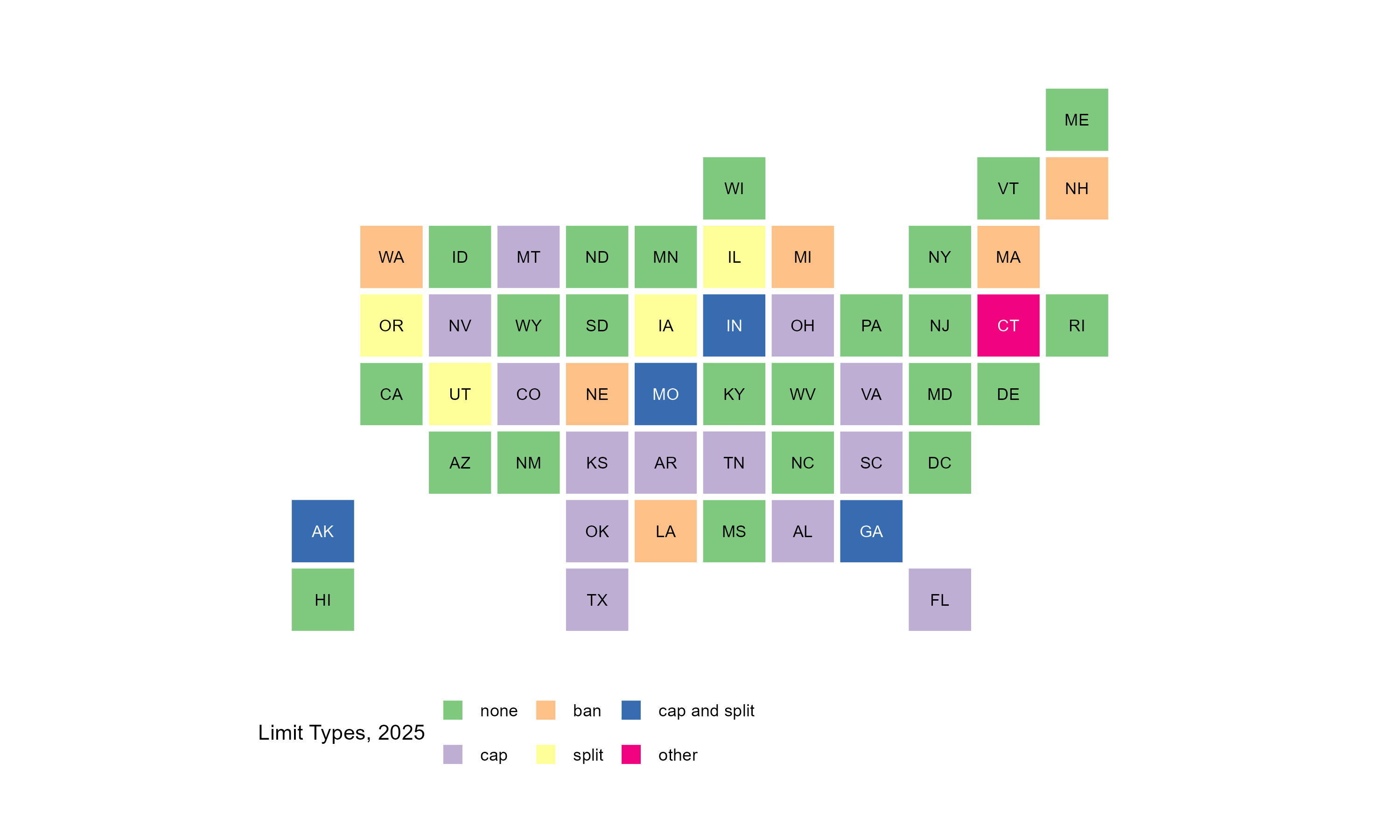

How much does Connecticut’s common-law approach differ from what other States do? Today, many States, mostly by statute, have banned, capped, or otherwise restricted common-law punitive damages (Kircher and Wiseman 2025, tbl. 4-1). Figure 1 depicts the limit types by State.

But no other State’s common-law has followed Connecticut’s approach. While some States permit accounting for attorney fees and costs in determining how much punitive damages to award (Litwin 2021), fees and costs are not the only basis for the size of that award.

Punitive Damages by Statute

What about when the Connecticut legislature authorizes “punitive damages” by statute? The State legislature can enact a statute that authorizes punitive damages that are differently calculated, just as it can (within constitutional limits) enact any statute that departs from the common-law approach to punitive damages.

For example, consider the Connecticut Product Liability Act, enacted in 1979 to provide single cause of action for all product liability claims under one or more theories of liability. Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S\S\) 52–572m(b), 52–572n(a). That Act provides:

Punitive damages may be awarded if the claimant proves that the harm suffered was the result of the product seller’s reckless disregard for the safety of product users, consumers or others who were injured by the product. If the trier of fact determines that punitive damages should be awarded, the court shall determine the amount of such damages not to exceed an amount equal to twice the damages awarded to the plaintiff.

Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S\) 52-240b. Although the Act doesn’t define what the term “[p]unitive damages” means, the Connecticut Supreme court has read it not to restrict punitive damages awards under that Act to Connecticut’s common-law rule. Bifolck v. Phillip Morris, 324 Conn. 362, 446-456 (2016). Notice, however, that the court decides the punitive damages amount and that amount is capped.

Elsewhere, the Connecticut legislature has authorized damages as some multiple of compensatory damages. E.g., Conn. Gen. Stat. \(\S\) 52-564 (treble damages for theft). Here, unlike punitive damages, once the fact-finder decides on actual damages for harm caused, neither judge or jury has any discretion as to how much the final award will be.

Conclusion

Here, we discussed Connecticut’s distinctive common-law approach to punitive damages.